The Rise and Fall of Soviet Studies at Lancaster

- EPOCH

- Dec 1, 2023

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 15, 2024

Jude Rowley | Lancaster University

In the years following the Second World War, universities on either side of the Atlantic were swept up in an interdisciplinary turn towards area studies as an increasingly popular field of research and teaching. Area studies sought to position itself as a more holistic academic endeavour than some of the more conventional disciplines in similar fields by uniting a focus on the language and culture of a particular region with a wider exploration of its society, politics, and history.

New interest abounded in regions from across the globe, such as China and the Middle East, but at the height of the Cold War in the early 1960s, no area attracted fascination quite like the Soviet Union. Some turned to Soviet and Russian Studies as ideological fellow travellers amid a growing student communist movement, but others did so out of suspicion of a mysterious Eastern enemy and a recognition that the dynamics of the global stage in the coming decades would be shaped by the Soviet Union. Unsympathetic depictions of the USSR and its citizens in popular culture played into these fears, embodied in James Bond villains like the stereotypically stern Rosa Klebb, but nothing focussed attention eastward more starkly than fear of nuclear attack. Official reports, like that of the Annan Committee in 1960, expressed an increasing concern that the British government, and by extension the wider population, seemingly knew so little about a state that in their eyes now possessed the power to destroy the world.

This increasing need to understand the Soviet Union translated into a recognition that Russian language teaching should be introduced at all levels of study. In 1962, Tam Dalyell MP, a stalwart of the Labour left, even called for a scheme to introduce the teaching of Russian to primary school pupils. It was the universities, however, that would serve as the real nucleus of this new interest in studying all things Soviet. A similar movement in the United States had previously seen the establishment in 1948 of the Russian Research Center at Harvard and an equivalent department at the University of California, Los Angeles. In the UK, however, it was not until the early 1960s that courses in Soviet Studies began to emerge as part of a wider effort to develop specialists not only in the Russian language but the workings of the Soviet system of politics and governance.

In the same period, major shifts in British higher education were underway. The early 1960s saw the emergence of the so-called plate-glass universities: new institutions that to some extent democratised higher education and opened doors for students from working-class backgrounds. Among these was Lancaster, established as a new university in 1964, though it would not have a campus for its early years of operation. As a new university in a historically overlooked region, Lancaster University saw itself as a radical new undertaking, keen to forge itself in the white heat of Harold Wilson’s technological revolution. Under the stewardship of its founding Vice Chancellor, Charles Carter (1919-2002), Lancaster in its formative years projected the impression of a place where things could be done differently.

With these overlapping contexts taken into account, it is perhaps no surprise that when the founding departments were chosen for the new Lancaster University, among them was the Department of Russian and Soviet Studies. Around the same time Carter took office as Vice Chancellor in April 1963, it was announced that courses in Russian and Soviet Studies would be offered to the first cohort of incoming Lancaster students. The architect behind the new department was D. Michael Waller (1934-2021), a former teacher at the local Lancaster Royal Grammar School and a firm advocate of Russian Studies, who would take office at the beginning of the 1964-65 academic year and would remain in the department throughout its relatively short existence. The department saw steady but respectable demand in its early years with a combined thirty students admitted in 1967 and 1968. Twenty of these undertook a longer four-year course with an initial language development component, having not previously studied Russian at A Level. This made Russian and Soviet Studies one of Lancaster’s smaller departments, but its degree schemes were not unpopular. For comparison, at this time sixteen Lancaster students a year were graduating with single-honours majors in Politics, making Russian and Soviet Studies a relatively competitive choice for incoming students.

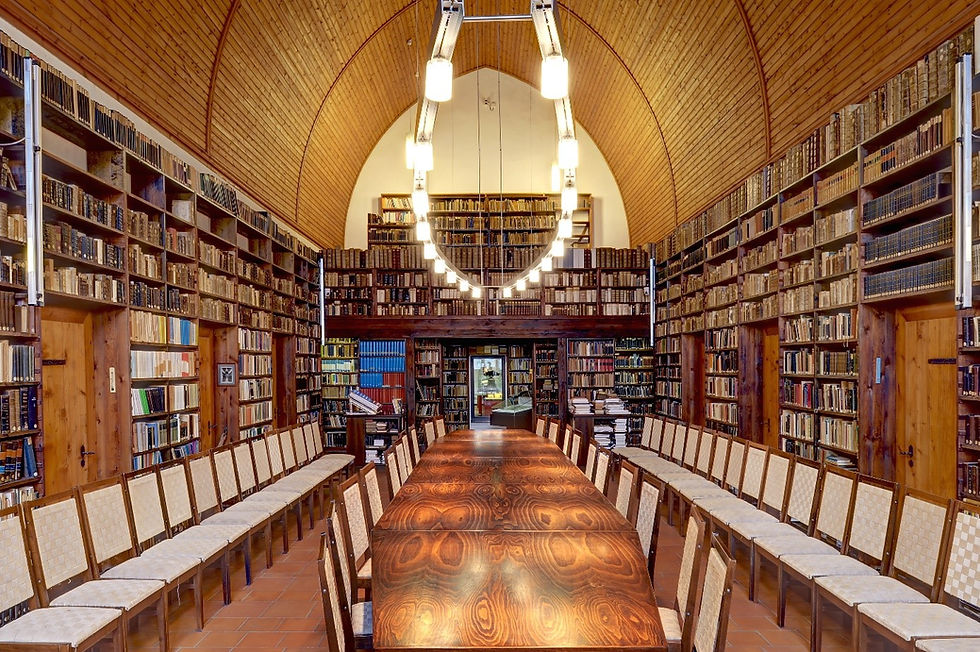

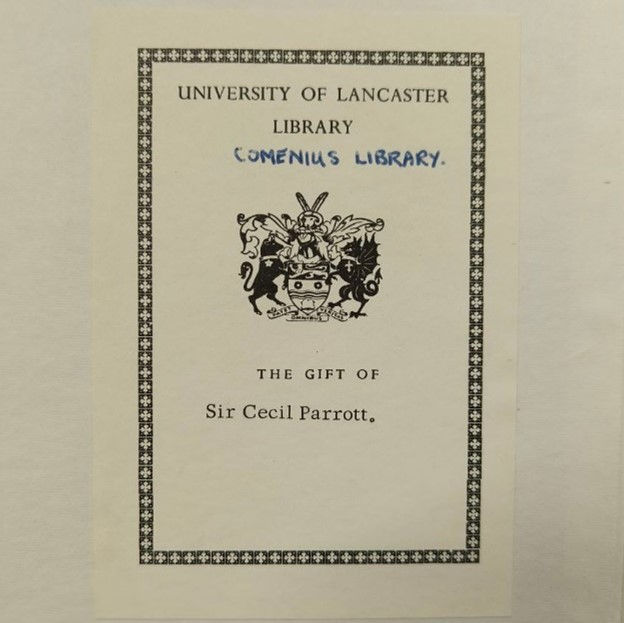

Alongside Waller, Russian and Soviet Studies soon made a major new addition when Sir Cecil Parrott (1909-1984), the British Ambassador to Czechoslovakia, took retirement from the Foreign Office in order to take up the role of Head of Department. Parrott’s biography reads like the kind of upper-class adventure story his Cambridge peers might have dreamed of, with stints as a tutor to King Peter II of Yugoslavia, senior British intelligence operative during the Second World War, and British Minister to Moscow (1954-1957) in the early years of the Cold War. Nonetheless, in 1966, Parrott traded Prague’s Thun Palace for office A44 in Bailrigg’s newly built Lonsdale College (since renamed Bowland North) and began a somewhat unhappy tenure as head of the nascent department.

Parrott was by no means a natural academic administrator, and by all accounts was often disinterested in the day-to-day practicalities of running an academic department. His tenure was marked by long periods of absence, in which the Deputy Head of Department, the celebrated Russianist historian Isabel de Madariaga (1919-2014), would take charge. Parrott’s time in the department was not without Bond-esque drama of its own. Rumours circulated that Parrott was a target of intelligence activity and he believed he was followed around the streets of Lancaster when hosting Eastern European exiles like Ota Šik. His long absences from Lancaster may have added to suspicions. In 1968, in one such absence, Parrott drove to Prague to acquire books for the departmental library and found himself caught up in the Prague Spring. Czechoslovak intelligence would later name Parrott as one of its principal culprits accused of involvement in fomenting an anti-communist coup in the country around this time. Whether he was using his position at Lancaster as cover for intelligence activities or not, Parrott escaped Prague after run-ins with the authorities and became perhaps expectedly disillusioned with Russian and Soviet Studies. On his return, his experiences led him to turn his attention instead to Czechoslovak Studies and the establishment of a new Department for Central and South-Eastern European Studies with an associated research institute, the Comenius Centre. In a sign of things to come, the University Grants Committee (UGC, the government advisory body responsible for directing the distribution of research funding) refused to support this new venture, and thus it would have to secure its own funding to keep its existence viable.

Throughout the next decade, struggles over funding would come to define the fate of Russian and Soviet Studies. With the onset of the Thatcher government in 1979, major shifts in higher education funding meant that the writing was perhaps already on the wall for a department and a field that had been forged in an academic revolution nearly two decades earlier. It was not to go without a struggle, however. In November 1980, the department faced its first run-in with major funding cuts when its abolition was debated by the Lancaster University Senate. On this occasion, the department was spared by forty-six votes to twenty-six, but the stay of execution would not last long.

The following March, the Conservative government introduced a White Paper calling for further spending cuts of an average of fifteen percent, distributed unevenly across universities. Lancaster’s projected cuts of fifteen percent marked a relatively moderate fate compared to other universities in the region, with Salford University facing a projected cut of forty-four percent at the same time. Nonetheless, drastic changes would be required to meet the demands of a much-weakened financial position. Though the implementation of these cuts was left to individual institutions, university managers were not free from governmental pressure. The UGC had been explicitly calling for the phasing out of ‘Russian-based studies’ at up to twenty universities since 1979 and now encouraged Lancaster to allow for the transfer of its department to the better-funded Universities of Oxford and Kent.

With this, the department would again find itself on the administrative chopping block. An estimated future deficit of £450,000 by 1983-84 meant several departments would face imminent closure. Under this pressure, when the Senate again debated the future of Russian and Soviet Studies, the decision to stop admitting new students would pass by a majority of a single vote. This brought to an end a vision of a modern field of study suited to the academic culture at Lancaster that had originated in the foundational years of the new university.

By this time, Charles Carter had retired and been succeeded by Philip Reynolds (1920-2009), a noted scholar of International Relations. Reynolds’ academic background, however, was not enough to save the department, and as Vice Chancellor he oversaw its closure. Students already enrolled in degree programmes with the department would be permitted to finish their studies, but they would be the last of their kind. The department continued to exist in a state of administrative purgatory as the Senate postponed votes to fully abolish it. According to the then Vice Chancellor, this was partly because few academic staff were willing to vote to put their colleagues out of a job. Nonetheless, in December 1981 the department was eventually closed after months of uncertainty. By the mid-1980s, it would cease operations and its staff would be forced to move elsewhere. Many found new homes in Lancaster’s other departments, whilst their colleagues moved on to other institutions.

Academics had fought unsuccessfully to defend not only their jobs but the very viability of the field. Staff in the department, including Parrott, expressed their frustration at the apparent lack of foresight in abolishing the department on the cusp of a key stage in the Cold War. These would be shared many years later by the department’s former Siberian specialist, Alan Wood, who remarked that the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea highlighted the dire lack of experts in studying the region, brought about by the closure of leading departments like that at Lancaster. As this suggests, the closure left a bitterness that endured long after the department closed its doors. Wood, for instance, would later dedicate a publication on the history of the Russian Revolution to the staff and students of his former department which he noted ‘like the Russian Empire, though with less reason, is also a thing of the past’. To understand this long-standing frustration, it is important to contextualise both the birth of the department and its premature decline.

The emergence of the Department of Russian and Soviet Studies was a product of its context, but so too was its demise. Forged in the heady days of a higher education revolution, it met its end with the onset of a wave of marketisation that would turn universities into the businesses that present-day students are more familiar with. For all the intrigue surrounding Parrott, the department was above all an intellectual endeavour aimed at pushing the boundaries of academia still marked by the insular elitism of the pre-war years. Lancaster embodied this sense of academic democratisation in its early years under Carter and so Soviet Studies epitomised what the new university would stand for. Its closure, on the other hand, summarised what Lancaster would come to embody in its later years. University managers and the new Conservative government argued that Soviet Studies was not viable as a resource-intensive department that did not attract the same popular interest as other fields. The administrative streamlining that came with the closure of Russian and Soviet Studies and a raft of other departments in the early 1980s would set the course for the decades to come. This was not a problem reserved to Lancaster. Russian and Soviet Studies courses across the country faced a similar fate. Across the London universities alone, for example, twelve undergraduate Russian Studies courses were withdrawn between 1979 and 1986.

Ironically, however, before the decade was out the 1989 Wooding Report would call for wider efforts at Russian Studies teaching to reflect the changing global situation, as had been the case a quarter of a century earlier. Those Russian and Soviet Studies departments that held out benefitted from additional government funding and attention of the sort that had not been seen for decades, with 10 new lectureships announced in June 1990. Birmingham University’s equivalent department, established around the same time as Lancaster’s, had faced similar pressures in the 1980s but survived the cuts of the Thatcher era and continues to endure to this day. Nonetheless, for Lancaster’s department, this came too late and its demise embodied a renewed turn towards an academic neo-liberalism far removed from the utopianism of Lancaster’s early years under Carter.

In its short lifetime, the department produced numerous research outputs that capture the nature and spirit of the work carried out under its auspices. These include Michael Waller’s study on the influence of the Russian Revolution on the Russian language (1972) and Michael Nicholson’s leading scholarly work on the writings of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, which led to translations of Solzhenitsyn’s work into English and the publication of the Solzhenitsyn Studies journal. Scholars from the department also contributed to the founding of the European Studies Review and Alan Wood’s later efforts would see the Sibirica Journal of Siberian Studies rise from the ashes of Lancaster’s department. Nonetheless, its legacy is marked by a profound sense of unfulfilled potential, especially in the context of the global events that followed its untimely demise. When coupled with the fact that institutional memory is naturally short at universities, with most students moving on after a three-year undergraduate degree, this has seen the department all but fade into historical obscurity.

Though the legacy of Russian and Soviet Studies at Lancaster has largely been forgotten, its sorry story remains an important illustration of the intersection between local or institutional histories and both global and national ones. Soviet Studies was a product of the overlapping contexts of the peak of the Cold War and domestic academic innovation: it emerged from a very particular moment in history. Its demise after a brief seventeen-year existence was no less a product of its times, and marks part of a thread that can be traced right through to present-day academia. While Lancaster’s Department of Russian and Soviet Studies may be long gone, its history remains more pertinent than we might imagine.

With grateful thanks to Marion McClintock MBE, Honorary Archivist of Lancaster University, whose recollections of the Department of Russian and Soviet Studies and the characters who shaped it helped inform the research behind this article. Responsibility for any errors or omissions rests with the author.

Further reading:

Marion E. McClintock, University of Lancaster: Quest for Innovation (A History of the First Ten Years, 1964-1974) (Lancaster: University of Lancaster, 1974).

Marion E. McClintock, Shaping the Future: A History of the University of Lancaster, 1961-2011 (Lancaster: University of Lancaster, 2011).

Cecil Parrott, The Serpent and the Nightingale (London: Faber and Faber, 1977).

Jill Pellew and Miles Taylor (eds.), Utopian Universities: A Global History of the New Campuses of the 1960s (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020).

Michael Waller, The Language of Communism: A Commentary (London: The Bodley Head, 1972).

Alan Wood, The Origins of the Russian Revolution, 1861-1917, Third Edition (London: Routledge, 2003).

Jude Rowley is a PhD candidate in International Relations (IR) at the Department of Politics, Philosophy, and Religion at Lancaster University and is a member of the Centre for War and Diplomacy. His research focusses primarily on the history of IR, especially its disciplinary historical sociology, with a view to addressing some of the historical silences that continue to shape the discipline.