We Can Be Heroes

- EPOCH

- Dec 1, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: May 27, 2022

Andrew Walmsley | Lancaster University

In the early stages of the Covid-19 crisis the Thursday evening 'Clap for Carers', when local residents stood on doorsteps and in streets to applaud NHS staff, keyworkers, caregivers, and fundraisers, became a regular event across communities in the United Kingdom. Amidst extensive coverage of these scenes, the words' heroism', 'heroes' and 'heroic' resonated across all forms of media and public discourse. It has seemed that anyone from any social class and walk of life can now be a hero. The celebrations of such heroism highlighted many issues in health and social care and, although these observances may ultimately be a driver for necessary change, they can also obscure the need for progress, shifting our collective attention away from issues of funding, resources, pay levels and management. Health care workers themselves have also noted that considering their actions as heroic may also imply that any Covid-related deaths in the sector are sacrifices in a greater cause rather than avoidable losses of lives. In many ways, our recent celebrations of the heroism of ordinary people is merely a continuation of a trend that already had considerable traction and can be traced back to the long nineteenth century. This era is well known as a time when contemporaneous great lives were celebrated and memorialised as Britain created a pantheon of heroic figures in celebration of nation and empire. These heroes were almost exclusively male and often naval and military characters such as Nelson and Wellington. Notable figures from other spheres such as the literary world were also invoked as emblems of patriotism as monuments to celebrate the lives of Robert Burns, Walter Scott and Lord Byron were also used to generate a sense of collective national identity. However, during this period, unlikely individuals, including women, also came to be valorised. Although a young woman from an unremarkable background, the lighthouse keeper's daughter Grace Darling also came to national prominence in 1838 after risking her life helping to rescue survivors from the steamship Forfarshire. A monument to her memory was raised over her grave in St Aiden's churchyard at Bamburgh in 1844 following her death in 1842. Her story was also outlined and embroidered in newspapers and biographies as she was set up as a national exemplar of dutiful heroism.

John Price and others have explored how, in the later Victorian period, more acts of heroism by ordinary people came to be celebrated. The British state and national organisations such as the Royal Humane Society and the Royal National Lifeboat Institution established medals celebrating heroic deeds outside the military or naval arenas. My own area of research centres on a memorial to lifeboatmen in St Anne's on the Sea in Lancashire which commemorates the entire crew of the lifeboat Laura Janet. Along with most of the crew of the Southport boat Eliza Fernley, they lost their lives in a disaster of December 1886 attempting to rescue the men of the German barque, Mexico.* This figurative depiction of a single lifeboatman erected in 1888 posits the everyday man as a hero, elevated literally on the promenade and metaphorically as a hero prepared to give up his own life for others.

Exemplifying the behaviour of the ordinary man or woman was used as a tool by various influential constituencies. In part, it became a didactic means of fixing notions of patriotic ideals and behaviour to which working people should aspire, but which did little to improve quality of life. In this way, my own lifeboat monument can be seen as projecting an image of aspirational virtue whilst obscuring the social conditions of the (predominantly) fishermen who crewed the lifeboats and were often living close to or below the poverty line.**

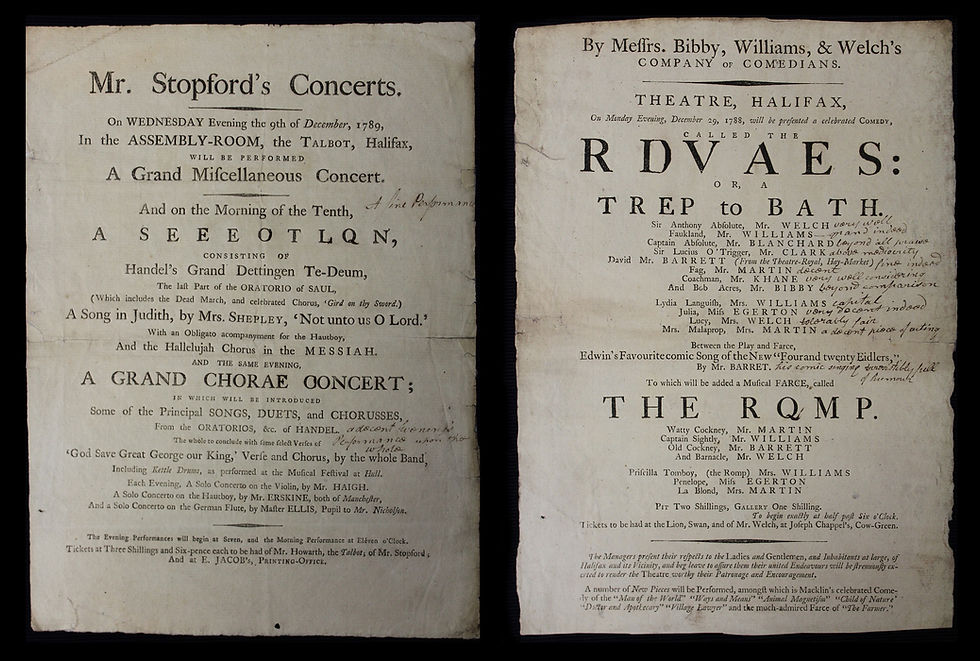

In contrast to this, Price has shown how a liberal, radical elite collectively used vehicles such as art and literature to celebrate 'Everyday Heroism' in a more progressive way. Many strands of thought fed into this 'movement' and, although it could certainly be paternalistic, it was used to promote the recognition of the contributions of the working classes to national life. The apogee of such commemoration is often considered to be G F Watts's Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice in Postman's Park, central London (unveiled 1900). Using memorial plaques, it champions those from ordinary backgrounds who had lost their lives in attempting to save others and Watts, one of the most noted artists of his day, had been lobbying for formal recognition of such unacknowledged heroism since the 1860s. Watts and others in his circle, which included two of the founders of the National Trust, the cleric and campaigner Hardwicke Rawnsley and the social reformer Octavia Hill, saw such recognitions of heroism as drivers to change social attitudes and create a more open and less divided society.

The plaques on Watts's memorial, were very much of the moment, celebrating heroic events and individuals of recent history in efforts to educate and enlighten. In the later nineteenth century, there was also a corresponding upsurge in publishing the stories of contemporary heroes with similar intent. Laura Lane's Heroes of Everyday Life was published in 1888, incidentally the same year that the St Anne's monument was unveiled. She retells the stories (exclusively of men and boys) of those such as Alfred Collins from Looe, Cornwall, a fisherman who risked his own life in entering a stormy sea to rescue a young crew member. The preface dedicates her work to the 'working men and boys of Great Britain' and Lane states, 'Whatever may be lacking in completeness of my work, there is certainly no lack of love, no lack of sympathy for the great working classes'. Such sympathy and admiration for the heroism of ordinary working people will often stop short of explicitly promoting practical and legislative changes to create a fairer society. But, in a wider context, it should be seen as being part of moves to push for improvements in housing, education and pay and working conditions. Indeed, Octavia Hill, supported by the likes of John Ruskin, personally developed practical, beneficial housing schemes for the working classes in London. Drawing parallels across a century or so of time is always problematic, but it would be nice to think that celebrating the heroism, particularly of low-paid care workers, might at last lead to a more practical appreciation of their work through appropriate levels of pay alongside respect and admiration. ---------------------- * The Lytham boat also went out on that night, and the men were able to rescue the crew. In terms of loss of life, this is still the most significant lifeboat disaster in British history. Lytham and St Anne's are close to each other on the Fylde coast of Lancashire. Southport is opposite both towns on the other side of the Ribble estuary. ** Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that the monument was paid for from surplus monies from relief funds which supported the dependents of the lost men. Further Reading

Lane, Laura, M. Heroes of Every-Day Life (London; Paris; New York; Melbourne: Cassell, 1888).

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 'Darling, Grace Horsley (1815–1842), Heroine'. [Accessed 22 October 2020]. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/7155.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 'Watts, George Frederic (1817–1904), Painter and Sculptor'. [Accessed 22 October 2020]. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/36781.

Price, John. 'Everyday Heroism in Britain, 1850-1939', in Extraordinary Ordinariness: Everyday Heroism in the United States, Germany, and Britain, 1800-2015, edited by Simon Wendt (Campus Verlag, 2016) 79–108.

Price, John, Everyday Heroism: Victorian Constructions of the Heroic Civilian (London, England ; New York, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014) http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=1577987.

Andrew is a former Local Studies Librarian and Community Heritage Manager who is studying part-time for a PhD in History at Lancaster University. The focus of his research is the promenade lifeboat monument at St Anne's on the Sea in Lancashire. He is exploring how it has featured as an important symbol in the town's history and how it can be placed within wider contexts of memorialisation and conceptualisations of heroism. Andrew is blogging about his research at: stonesermons@blogspot.com.