Tackling the Archives: The PAST

- EPOCH

- Dec 1, 2020

- 9 min read

Daniella Marie Gonzalez | Kent University

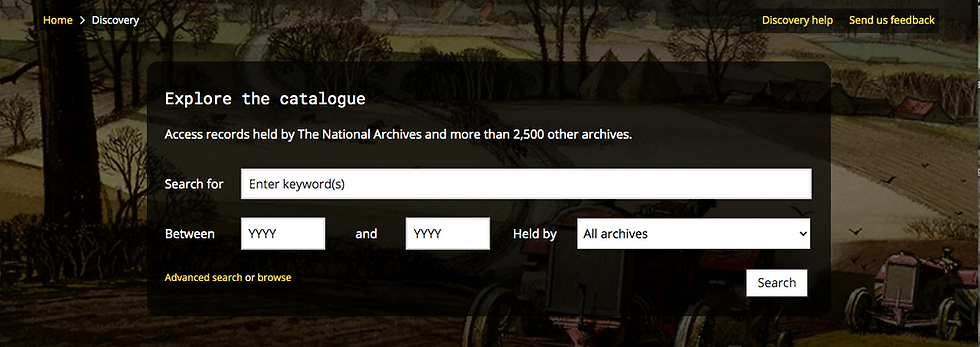

Archival research is all about knowing how to find your primary materials and extracting information from them, which, unlike secondary research, demands a different set of skills. It requires the confidence to work and handle eclectic collections situated within museums, galleries, archives and libraries, to name a few. Locating, identifying and physically handling items are the main challenges any postgraduate starting their career as a scholar, regardless of discipline, faces when embarking their research journey and is something that many of us can immediately relate to. I certainly do, and the opportunities presented to me during the early stages of my doctorate provided me with the perfect chance to develop my research skills within the archive. Between January and March 2017, I undertook a placement with the Medieval and Early Modern Team at The National Archives (TNA) to gain more experience in research using archival records and to understand what working with medieval and early modern records was all about. One of my highlights during this placement was contributing to and taking part in TNA’s PAST workshop on medieval and early modern records, which took place from the 24th to 25th January 2017, and this is what I’ll be focusing on throughout this piece. PAST stands for Postgraduate Archival Skills Training and is held on a yearly basis and was developed by records specialists working at TNA. These sessions are designed to provide postgraduate researchers with the necessary skillset needed to work with the archival records that are at the heart of their research. Whilst sessions are held for those studying modern history, I’m going to discuss what skills those working with pre-modern records need, the types of sources they’re exposed to and how to use these records to undertake research. I will also be referring to the Medieval and Early Modern Legal Records workshop held by TNA’s Medieval and Early Modern team to demonstrate how knowledge and experience of using TNA’s legal record collection can enhance postgraduates’ understanding of how to use these materials for their research. Using archives: resources and onsite materials at TNA Key to any researcher wanting to use archival collections for research is an understanding of how to use an archive’s catalogue. Catalogues are, of course, a crucial step in documenting collections and it is here that you would find information that could pique your interest, give you key details about your source (the year it was created, subject matter of the item, and language its written in for example). However – and I have very much been here myself – using a catalogue when you first start your research journey is not always the easiest of tasks. To get past this hurdle, members of the Medieval and Early Modern team gave an introduction to Discovery, the online catalogue. The ins and outs of Discovery were outlined, as well as a demonstration of its different functions and the positives of using the advanced search. Discovery also provides references for not only the records held at TNA, but also other documents held in archives across the UK. Discovery also has other extremely useful options for researchers, such as enabling individuals to export their results into an excel sheet as a way of managing information. Since learning about this particular feature, searching for and making a list of records for my own research has become much easier and more effective.

A number of online resources were also utilised to illustrate the variety of resources that can be used at TNA. These include and are not limited to: State Papers Online, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and ProQuest. Another good example of these resources is the E 179 taxation database, which contains information from records known as the ‘King's Remembrancer, particulars of account and other records relating to lay and clerical taxation’. This database is useful for researchers whose studies have an agricultural or economic focus.

Linked to this, postgraduates were also treated to a talk by Dr Heather Pagan, a member of the editorial team of the Anglo-Norman Dictionary. She provided us with a brief but detailed introduction to Anglo-Norman, the type of French spoken and written in England c.1066 to the mid-fifteenth century. As a historian of late medieval England, understanding medieval French is a key part of my research and knowing where to find these resources, as well as how to use them, was a vital part of my archival skills training as it gave me the tools needed to undertake my archival research. This highlighted to me that learning how to carry out archival research was not just about viewing and reading the archival records but, also, about talking to the experts. It was at this very session that I learnt from Dr Paul Dryburgh about C. R. Cheney’s Handbook of Dates, a reference book that provides a break-down of regnal years, as well as important historical events and when they occurred – without this I would have been lost when it came down to regnal years!

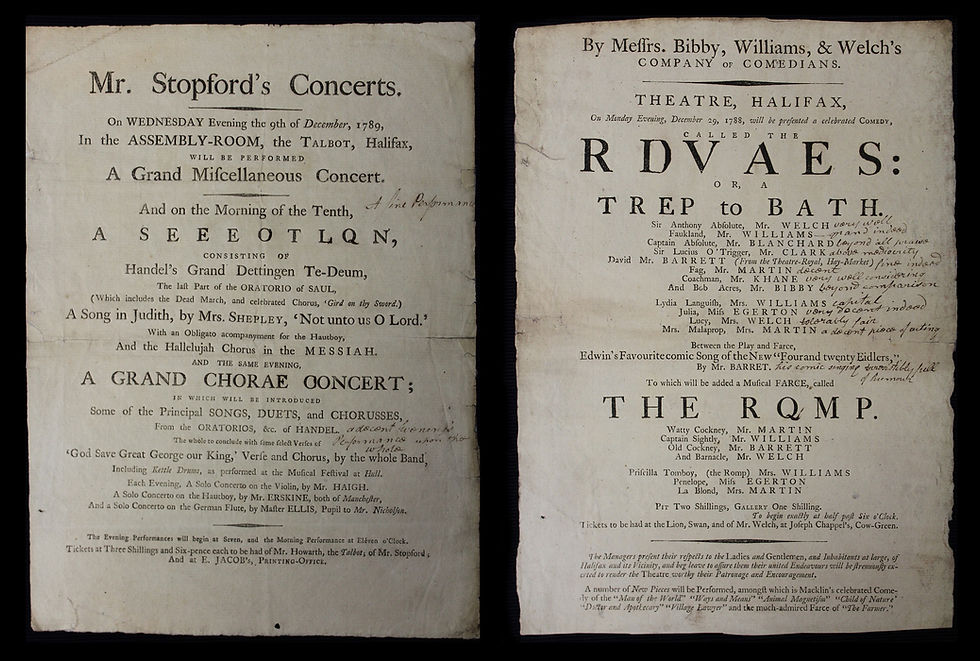

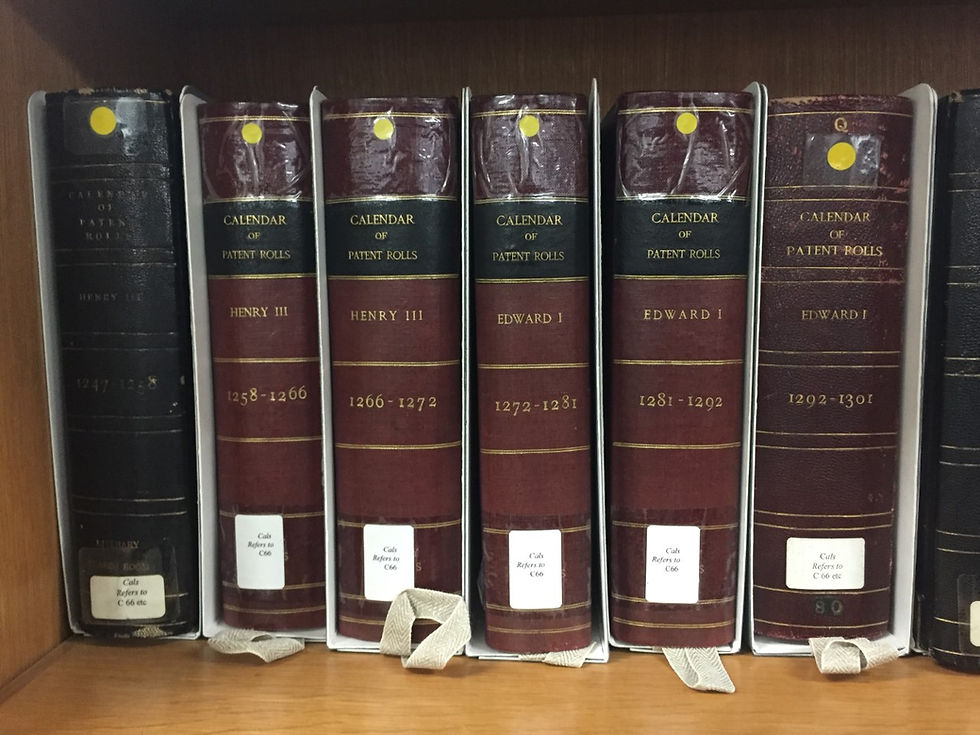

Having learnt the value of using online sources for archival research, the team also ensured that postgraduates understood how to use onsite resources within the Map Room, the reading room in which all documents pre-1689 are viewed. Even more imperative was learning to use the finding aids located here. These aids are an extremely useful tool for researchers needing some extra help locating documents, particularly when that involves converting old references to the current document reference. Within the MAP Room, there are also several files that give detailed descriptions of the different records series within TNA; these offer an outline of the type of records, the date range for when these records were produced and, occasionally, the offices in which they were produced and editions of the records themselves. Content and context of medieval and early modern archival records As I’m sure any medievalist or early modernist knows, TNA holds a rich corpus of material that spans a myriad of centuries. During this session, we were given a taste of their collection, with records, ranging from charters, petitions and parliament rolls, dating from Anglo-Saxon England to the seventeenth century. PAST, therefore, gives postgraduates the experience to examine and get to grips with the nature of medieval and early archival documents, specifically four types of records – grants, deeds, and petitions; letters; accounts; and legal records. It’s important to know not just what the records you are looking at are, but also where they come from and what the information these records hold tell you about the broader context of the environment in which they were produced. Key to the sessions, therefore, was understanding the way that English royal government functioned and what stories the records could tell us about governance and the Crown throughout the medieval and early modern periods. Whilst a large portion of the sessions was dedicated to reading and understanding the documents, some time was spent explaining and engaging with how these documents functioned and what (legal) channels they went through. From these records, therefore, we can start piecing together how the criminal justice system functioned, the rise of equity, the differences between local and more central courts (like church local courts and the court of King’s Bench), and where this information was recorded. These materials also give us a window into court administrators and multiple judicial figures, such as justices of the peace, and those who made a note of criminal cases, fines, and debts.

Royal government, of course, extended from the centre into the peripheries making it just as important to understand local contexts and how this formed part of England’s wider national story. Archival records, therefore, do not just offer a lens through which to view royal government at work, but also how government extended into beyond the courts of Westminster into the localities. Manorial records, for example, are an excellent insight into this history and the team gave those present an overview of how medieval local justice worked through examining the manorial court system. These records are filled with information that does not only uncover how the judicial system functioned, but also how late medieval and early modern society worked and about social practices of the time, especially those who made up the day-to-day infrastructure of Westminster’s legal system. As demonstrated in the below image, scribes were not just the keepers and creators of legal memory but left their marks on these documents; these identify who they were and are even reflective of the cases they were recording. It raises questions around whether this is what scribes did when work was tedious, and a creative outlet was needed – even scribes doodled!

Understanding dates, numbers and monetary values within the medieval and early modern worlds is also necessary for any PhD student to know, and we were treated by the team to talk outlining how to work out regnal years and the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. Going over these with the team meant that we could understand how to order dates chronologically, assess historical accuracy through dating and work out numerical values within TNA’s archival collection.

Attending these sessions and having the nature of archival records put into context was a great way for me enhance my understanding and knowledge of political culture, the language that was employed by administrators to illustrate what good governance was, and the channels that records, such as petitions, went through.

Handling and reading medieval and early modern documents

Consulting records, perhaps, is one of the most daunting challenges postgraduates in the early stages of their research will face (and I can assure you that this was certainly the case for me). Whilst the team had provided some facsimiles or certain records (but which were just as helpful when it came down to practising our palaeographic skills!), we had several original records in front of us, which we were given the chances to handle. These ranged from, but were not limited to, collections of early modern letters to Plea Rolls.

Equally important is the ability to familiarise yourself with different scripts across different types of documents. Using the four abovementioned types of records, the team organised a series of palaeography exercises after giving lectures on the types of sources with which we would be working. Records that we used included the Lisle Papers (TNA, SP 3), the correspondence written of Arthur Plantagenet, whereby exchanges between himself and his wife, Lady Lisle, such as the one below, were examined.

The Lisle Papers are just one of many series of letters held at TNA (you’ll also be able to find the Stonor Letters (C 47) and the Cely Letter (SC1 and C 47)) and were an excellent example for students to become accustomed with sixteenth-century palaeography, as well as the nature of documents that form part of the collection of State Papers.

The team also taught those present how to look for information quickly within documents, doing so by asking students to pinpoint certain words, place names and values within the record. Accounts were a particularly useful source in carrying out this exercise, and the team had prepared an Exchequer account, E 101/459/22, which is a record used during the sessions on accounts. This particular account described the dissolution of Chertsey Abbey and proved to be an excellent record for students to put their palaeography skills to the test. For example, one place that was particularly easy to spot once you’re accustomed to the script was ‘Hampton Court’. Scanning for information quickly by looking out for key terms, dates, and places is one of the best tips I’ve ever been given and one that I still employ when carrying out archival research.

This exposure to original materials (as well as practicing from facsimiles) afforded postgraduates the chance to gain an insight into what to expect in these documents. These are exactly the kind of sessions during which postgraduates can get to grips with the way that archives can be used for research. By attending PAST, postgraduates are able to better understand the formulaic nature of different documents, how to work out abbreviations, and types of script, as well as how these documents were set out and archived by their contemporaries. If you’re a postgraduate student undertaking an MA or PhD in medieval and early modern studies, I cannot recommend these sessions enough. They’re an excellent way to build up your confidence, get to grips with palaeography and Latin, and to be taught by the most amazing team of medievalists and early modernists. PAST skills training also provides several benefits beyond the PhD, assisting with future careers – whether you later work in academia, archives, museums or other heritage sectors, PAST boosts both your skills and profile as a professional researcher. ---------------------- Dr Daniella Marie Gonzalez is the Social Media Fellow for the British Association for Local History, Communications Officer for ARA’s Section for New Professionals and Co-founder and Editor of MEMSLib. She completed her PhD at the University of Kent in 2020 and researches the history of medieval London, focusing particularly on political language and civic records. Dr Gonzalez is currently undertaking a qualification in Archive Administration from Aberystwyth University and is pursuing a career as an Archivist and is a serial contributor for EPOCH. Twitter: @DeeGonz92 Website: The Archive Diaries