Joseph Hall – The First Opponent of Early Modern Travel Culture

- EPOCH

- Dec 1, 2023

- 7 min read

Mikhail Vsemirnov | University of Padua

Today, the value of travelling is unquestionable. Our current tourism culture has left no doubt about why one should travel to a particular part of the world. However, this was not always the case. The European world saw an intensification of mobility only in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Travelling became possible for a broader public and produced a lot of information about distant lands. As a result, this period left a lot of literature which offered some advice on how proper travel should have been organised. The emerging popularity of travel, however, brought a lot of debate. On the one hand, travelling was perceived as an educational opportunity based on the pursuit of knowledge. On the other, some feared it because of the entertainment and debauchery that usually accompanied travellers.

Critics saw travelling not as an opportunity but as a distraction, a dangerous enterprise that should have been avoided for its moral implications, lack of security, or the temptations along the way that could lead a decent person astray from the right path. Historians are aware of these opinions. However, they never focus on them directly. By focusing on voices critical towards voyaging in early modern Europe, I would like to show that the travelling experience in the past was not – as traditionally studied – an opportunity but a dangerous and unnecessary enterprise. To start this discussion, this article focuses on one example of a negative attitude toward travelling and gives an answer to why such an idea emerged.

To begin with, I would like to start with the main protagonist of this paper – Joseph Hall (1574–1656), an English bishop and satirist. He was born at Bristow Park, Leicestershire, in July 1574. Hall received his early education at the local school and was sent by his father (1589) to Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Two of his works were dedicated to the culture of travelling. The first writing, Mundus Alter et Idem (Another World and The Same), was written in Latin around 1598, then translated into English and published in 1605. The second was Quo vadis? A Just Censure of Travell, published in 1617. The Quo vadis? was initially written and published in English not only because it was created in a different genre for another audience but also due to the rising popularity of educational travelling to continental Europe among British aristocrats at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

Being taught in one of the centres for training protestant preachers, bishop Hall played a significant role in the English Reformation. The publication of his works coincided with the period of his active involvement in the spread of Protestantism in England and Scotland. For example, Quo Vadis? was published the same year the Five Articles of Perth were imposed to integrate the Church of Scotland into that of England. Joseph Hall even accompanied James VI on his trip to Scotland to defend the articles and push their imposing. Thus, his works demonstrate in many ways a strictly Protestant vision of the meaning of travel.

Mundus Alter et Idem was one of Hall’s early works, intended as a university exercise, and apparently never planned for publication. When it first appeared in 1605, it was published without its Hall’s consent. The book is an early example of dystopia published under the title The Discovery of a New World. Mundus focuses on society’s degradation and is designed to satirise the failings of contemporary Europe. It is structured as a travel diary written by a fictional character Mercurius who visits different lands and describes them. The choice of the name was not coincidental. It was common to give fictional characters well-known names from mythology to give more meaning to a work. In this case, Hall chose a god of messages, communication and, more importantly, travellers. Mercurius, the main character, travels through such places as Eat-allia and Drink-allia, Fooliana, Womandecoia, or [sic] Hermophradite Island. All lands are aimed at mocking and accusing certain characteristics of human nature. In each case, the work focused on a particular vice and hyperbolised the structure of one society according to that nature. For example, in Drink-allia, Mercurius gives a description of local laws and rules by referring to a list engraved on a stone in the central city. According to law thirteen, for example, “That hee that mixeth water with his wine, bee sent to suppe amongst the dogs.”

This way, Joseph Hall inverted the moral rules in the society he described and hyperbolised them enough to demonstrate to the audience why certain vices should be controlled or forbidden.

Despite being written as an itinerary, the work was intended to question the very idea of travel. At the beginning of the work, the protagonist explains the purpose of his journey and engages in a dialogue with two friends who were travelling with him. He states, “I see not (if this bee true) any profit or worth in the world, contained in travell.” And further:

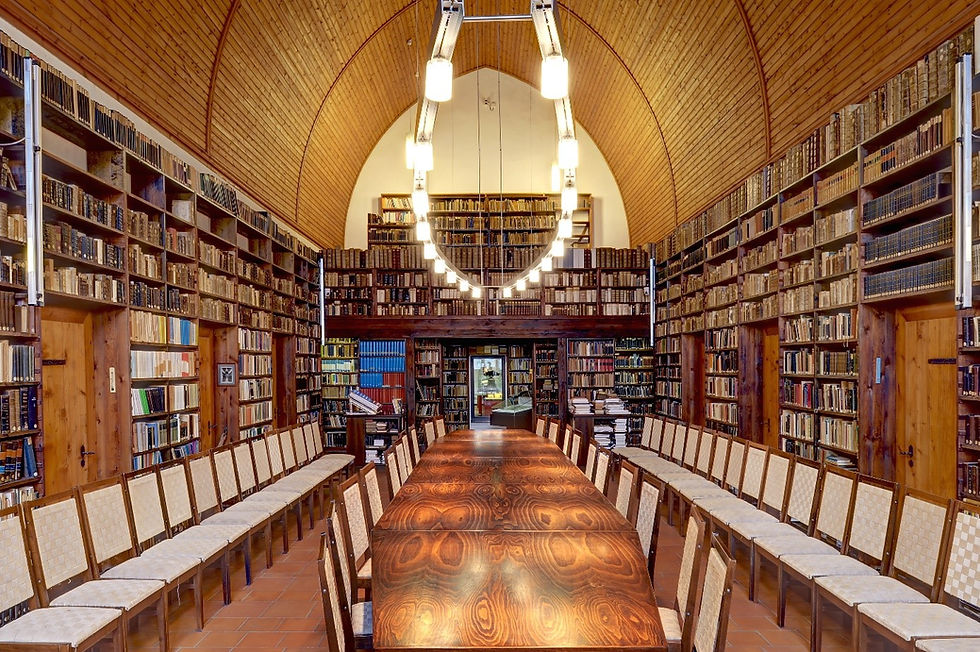

And what is there in all the knowne world, which mapps, and authors cannot instruct a man in, as perfectly as his owne eyes? Your England is described by Cambden: what understanding man is there, that cannot, out of him, make as perfect a description of any cittie, river, monument, or wonder in all your Ile, as well as hee had viewed it in person himselfe?

Thus, Joseph Hall’s writing worked on two levels. First, it moralised the human experience by pointing out what evil habits and vices can lead to. Second, the book questioned the value of travel practices, preferring a more authoritative theoretical learning based on written sources.

Hall then developed these ideas in his second work on travelling, Quo Vadis? A Just Censure of Travell published in 1617. This piece was an oration where the author appealed to all who plan to travel, with the goal of protecting them from the ‘wrong’ way. In his reasoning, Hall attacked a certain type of travel:

It is the Travell of curiosity whereof my quarrell shall bee maintained; the inconveniences whereof my owne senses have so sufficiently witnessed, that if the wise parents of our Gentry could have borrowed mine eyes for the time, they would ever learne to keepe their sonnes at home.

From his point of view, curiosity led to aimless wandering primarily for the search of entertainment. Here, Hall’s beliefs stem from the ideas of neostoicism. This philosophical movement stated that the basic rule of life is that a person should not follow passions, which leads to mistakes and faulty reasoning, but instead, submit to God as a moral absolute. On the other hand, Hall may also have been influenced by his own travel experiences. In 1605, he accompanied Sir Edmund Bacon on an embassy to Spa. Later, in 1616, he travelled to France, accompanying James Hay, Lord Doncaster, on a diplomatic mission to congratulate Louis XIII on his marriage. Next year, he accompanied James VI to Scotland to defend the Five Articles of Perth. Briefly describing this experience in his autobiographical notes, he often mentioned his fear of being attacked by bandits or getting into other trouble. Such fear is not surprising because travelling was influenced by the danger that always accompanied travellers. Hall’s trips took place in a context of instability; the early seventeenth century saw the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War and tensions between papal authority and the French palace left over from the Wars of Religion. Besides, voyages brought unexpected encounters with individuals from other social or religious groups. Being a strong protestant, Joseph Hall also wrote about several conflicts he had with Catholics.

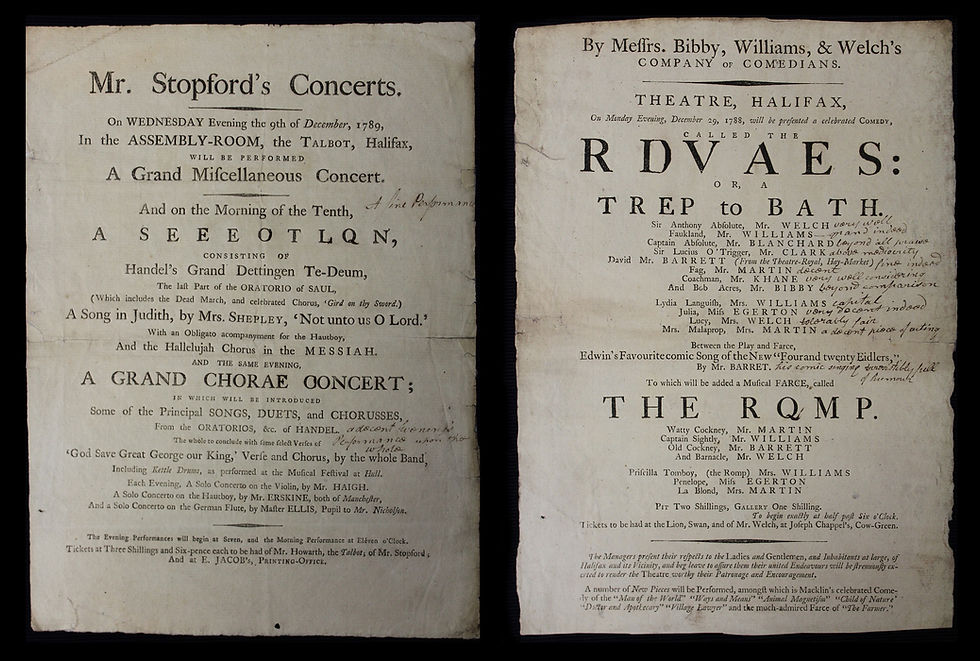

Hall’s works, especially Quo Vadis? were popular among their audience. In 1628, the work was translated into French. Later, in 1674, excerpts from the work were published as a poster and displayed to the public at St. Paul’s Church Yard in London. It contained fifty-six quotes which were meant to have the greatest effect on the public, such as

“Know therefore that nothing is more prejudicial than speed;”

“I have known some that have travelled no farther than their one Closet, which could both teach and correct the greatest Traveller;”

“A good Book is at once the best Companion, and Guide, and way, and end of our Journey.”

Obviously, Joseph Hall was not the only one who expressed criticism towards travelling. Before him, Roger Ascham’s The Scholemaster (1570) dedicated one section to pedagogical concern for travelling being a distraction from education. In his Methodus Apodemica (1577), Theodor Zwinger, compared the utility and inutility of different types of voyages to sustain an objective position towards the topic of discussion in a humanist manner. However, the English bishop seems to be the first to take a strong position. An active critic of educational travel, he prioritised knowledge gained through classical learning from books. In criticising curiosity-based travel, he inclined his reader toward a more thoughtful and planned experience. As the voice of religious fears of the expanding popularity of travel for education or leisure, Joseph Hall represents protestant attitudes towards travelling, which continued to circulate in the following period. This attitude towards travelling found its source in a combination of Protestant ethics, the ideas of neostoicism, and the very mobility that was often accompanied with danger and unexpected encounters.

Further Reading:

Enenkel, K.A., Jong, Jan L. de (eds.), Artes Apodemicae and Early Modern Travel Culture, 1550-1700 (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2019)

Stagl, Justin, A History of Curiosity: The Theory of Travel 1550-1800 (London, New York: Routledge, 1995)

Ord, Melanie, Travel and Experience in Early Modern English Literature (New York: Palgrame Mcmillan, 2008)

Warneke, Sara, Images of the Educational Traveller in Early Modern England (Leiden: Brill, 1995)

Gelléri, Gábor, Willie, Rachel (eds.), Travel and Conflict in the Early Modern World (Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2021)

Mikhail Vsemirnov is a PhD researcher in History at the University of Padua in Italy. He is working on travel advice literature and travelling practices in early modern Europe to understand what challenges voyaging brought in that period, as well as why certain groups criticised this practice.