From Maps to Apps: Over the Hills of the English Lake District

- EPOCH

- Mar 1, 2023

- 7 min read

Liz Woodham | Lancaster University

Fell-walking is the practice of walking over rough ground, chiefly the mountainous country or fells of the Lake District National Park (LDNP) and parts of Scotland. Fell walking has become an important leisure pursuit in a landscape that is globally, as well as nationally, significant; Lake District guidebooks were even cited as evidence in the successful designation of the area as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2017. While fell-walking has been a popular pursuit for hundreds of years, two watershed moments in cartography shaped the illustrated walkers’ guides to the English Lake District, and thus fell-walking itself, into what we know today.

First, the Ordnance Survey (OS) completed mapping the district by 1868. Accurate and usable maps altered what was expected of a guidebook and enabled pedestrians to explore the uplands on foot without hiring a physical guide. Before this point readers were generally cautioned to hire a physical guide when venturing into the uplands of the district, largely due to the vagaries of mountain weather, the uncertain nature of the ground to be covered, and the dangerous nature of the fells themselves. Guidebooks in the first half of the nineteenth century often drew attention to the fate of the artist Charles Gough who was killed in a fall from Helvellyn in 1809 whilst climbing the mountain unaccompanied. An early map from Thomas West’s A Guide to the Lakes in Cumberland, Westmorland and Lancashire, first published in 1778 and widely recognised as the first guidebook to the area, reinforces why such advice was necessary.

Detailed route directions for walkers accompanied by accurate maps assumed prominence in Herman Ludolph Prior’s Ascents and Passes In The Lake District Of England (1865), Henry Irwin Jenkinson’s Practical Guide To The English Lake District(1872), and M.J.B Baddeley’s Thorough Guide To The English Lake District (1880). These guidebooks typically included fold-out and sectional maps of the district which accompanied content that was increasingly practical and focused on pedestrian exploration of the fells. The cartography in Baddeley’s guidebook was particularly important in encouraging the leisure pursuit of fell walking.

Maps such as this example by the Edinburgh map makers and publishers Bartholomew represented the first use of printed layer colouring to denote contours rising in 500 feet increments up to 2,500 feet. This development helped Baddeley’s readers to better understand the height and potential difficulty of the landscape. Modern Harvey maps utilize a similar design.

The change in the methods guidebooks could use to direct walkers resulted in physical guides being dispensed with and the list of fells and ascents expanded. Guidebook recommendations show that the type of intrepid walking represented by ascents of the high, rocky, and exposed ridges of Striding Edge on Helvellyn and Sharp Edge on Blencathra had come within the reach of the regular visitor from the 1860s. Whilst Striding Edge was no longer described as perilous, continued references to mountain accidents and mishaps indicated that the skills to use the more detailed maps included in guidebooks took a while to develop (and continue to do so).

The re-publication of the two-and-a-half-inch OS maps from 1937- 1961 represented the second watershed moment. The detail that these maps included on the complex and rough Lake District landscape enabled Alfred Wainwright (1907-1991) to make his own accurate cartography. Many people view Wainwright as the godfather of modern fell walking. The Wainwright Society was founded in 2002 ‘to keep alive the fellwalking traditions promoted by Alfred Wainwright through his guidebooks and other publications and to keep faith with his vision of introducing a wider audience to fellwalking and caring for the hills’.

Wainwright’s seven-volume pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells were first published between 1955 and 1966. The Pictorial Guides are noteworthy for being completely handwritten and illustrated, with text and over 3,600 illustrations based on Wainwright’s solo fell walking explorations over a thirteen-year schedule that he planned meticulously.

Wainwright read maps for interest and drew his own for the Pictorial Guides. He contended that the widely used maps by the OS and Bartholomew could not be relied on in the matter of footpaths on the ground, which was of the utmost importance to the fellwalker. Rights of way shown on OS maps were not necessarily the paths that appeared on the ground. Wainwright criticised Bartholomew’s maps for the more serious defect of showing paths where they did not or could not exist - most worryingly over precipices.

Accurate maps were of such importance to Wainwright, both as a fell walker and a guidebook writer, that he fully integrated them with the text of the Pictorial Guides instead of positioning them as accessories to it in the manner of previous guidebooks. As an amateur cartographer, he was free to vary the scale of his maps depending on the complexity of the ground he wished to represent and show landscape features in his own style. His map key included three types of footpaths to better inform the walker on the ground (Good – distinct enough to be followed in mist; Intermittent – difficult to follow in mist; Route recommended but no path – with directional arrows if recommended one way only).

Wainwright’s innovative ascent diagrams and the way in which he structured the Pictorial Guides supported the primacy of his mapping. His ascent diagrams adopted imaginary or impossible viewpoints hovering above the ground to give a walkers’ eye view of the terrain.

The structure of the Pictorial Guides as a curated collection of 214 fells within the boundaries of the LDNP allowed Wainwright to include a variety of maps. Each fell was given a separate chapter with a consistent structure- maps in simple plan view which pinpointed its location, detailed topographical maps, ascent diagrams, maps of the summit (if the ground was particularly complex and rocky), and sketch maps of ridge routes.

Wainwright’s distinctive cartography is key to why his Pictorial Guides have been in continuous use for over seventy years and explains some of the censure they have attracted. Graphic designers have praised the Pictorial Guides for the clarity of their information design and likened their intuitiveness to the London Underground map. Other users are put off by the idiosyncratic nature of Wainwright’s approach. Were his maps and diagrams and accompanying text so easy to follow that they attracted too many visitors to the district, leading to the erosion of footpaths? Are the Pictorial Guides so detailed that they left nothing to discover in the uplands? Or by contrast, does Wainwright’s cartography lead the unwary walker astray?

The ongoing tension between the preservation and protection of the district revealed in some of the criticism of the Pictorial Guides is almost as old as the print tradition of English Lake District guidebooks. John Wyatt, the first warden of the LDNP suggested as early as 1966 that Wainwright’s guidebooks were already outdated and were the cause of mountain accidents and footpath erosion from too many visitors. Wainwright rejected this, claiming instead that there would be more incidents without his guidebooks. His contemporary, the climber and writer Harry Griffin, suggested that Wainwright’s guidebooks were in fact too complete and risked taking away the joy of discovery of the fells. Wainwright contended that visitor numbers would have increased anyway, and erosion of footpaths was not due to the increasing popularity of fell walking but clumsy walkers, particularly those in groups who widened footpaths by walking side by side to converse.

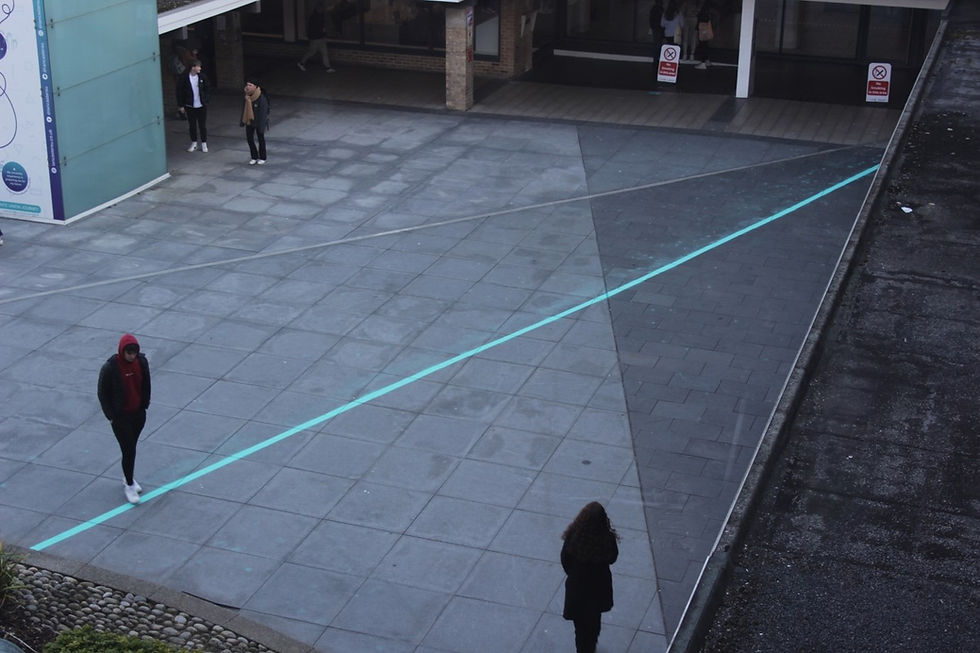

As growing numbers of people take to the uplands of the district today cartography has been drawn into another debate which centres on the balance between providing information and guidance and allowing for personal decision-making. The website of Keswick Mountain Rescue Team states that ‘Occasionally paths and rights of way are badly placed on OS maps’ and singles out Wainwright in some rescues. The popularity of ‘doing the Wainwrights’ – the 214 summits included in the Pictorial Guides - has led some walkers to go astray or underestimate the difficulties of the lesser heights of Barf and Catbells near Keswick in the northern Lake District.

Ultimately any guidebook or map is only as good as its reader. In an age of digital mapping users of traditional guidebooks and maps are getting fewer. Despite the Lake District National Park Authority employing three Fell Top Assessors to climb Helvellyn daily from November to Easter to report on weather and ground conditions and give advice on mountain safety, walkers still get lost - or worse. Zac Poulton, one of the Assessors, notes that most walkers he encounters on Helvellyn don’t carry a map let alone a guidebook, relying instead on navigation via various apps on their mobile phones or increasingly on being part of a group expedition initiated by an Instagram influencer. Cartography in illustrated walkers’ guides shaped the development of fell walking in the English Lake District but may well be less relevant to its future.

Further reading:

Baddeley, M.J.B., The Thorough Guide To The English Lake District (London: Dulau & Co., 1880).

Davies, Hunter, Wainwright the biography (London: Michael Joseph, 1995).

Hutchby, Clive, The Wainwright Companion being an illustrated collection of fascinating facts, statistics, trivia and opinion – based on the guidebooks to the English Lake District of A. Wainwright (London: Frances Lincoln, 2012).

Jenkinson, Henry Irwin, Jenkinson’s Practical Guide To The English Lake District (London: Edward Stanford, 1872)

Wainwright, A., A Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells being an illustrated account of a study and exploration of the mountains in the English Lake District, 7 vols (London: Michael Joseph, 1992-97).

Wainwright, A., Fellwanderer, The story behind the guidebooks (Kendal: Westmorland Gazette, 1966).

Liz Woodham is a part-time PhD researcher at the University of Lancaster studying how English Lake District pocket guidebooks and the leisure practice of fell walking in the area have shaped each other from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries. She has walked 213 of the 214 Wainwright summits in the district with a map and without an app, though there are several times when the latter could have been useful...