Emyr Estyn Evans and the Making of Regional Heritage in Northern Ireland

- EPOCH

- Sep 1, 2025

- 9 min read

Carys Tyson-Taylor | University of Leicester

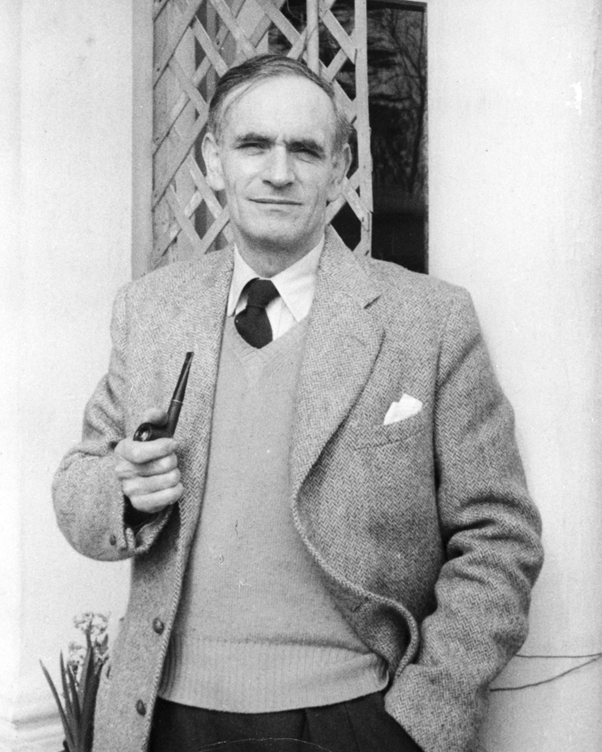

In 1963, a two-roomed thatched cottage - originally located at the foot of Binevenagh Mountain in County Derry/Londonderry - was reconstructed in Cultra, just outside Belfast. This modest dwelling was not a mere preservation project, but rather it was the first building exhibited at the Ulster Folk Museum. The dwelling, known as Duncrun Cottier’s House, marked the physical realisation of a vision held by Emyr Estyn Evans (1905-1989). Evans’ work laid the intellectual foundation for the museum’s establishment and early development. As a geographer, folklorist, and archaeologist, Evans argued that Ireland – particularly the province of Ulster – was made up of miniature environments encompassing distinct regional landscapes, traditions, and ways of life that developed over centuries. For Evans, regional difference was not a barrier, but a concept through which to better understand the continuation of historic cultures in Ireland.

Evans’ ideas shaped the Ulster Folk Museum’s founding ethos and historical interpretations. An analysis of two contrasting case studies of buildings realised onsite, Duncrun Cottier’s House and Corradreenan Farmhouse, illustrates how the museum gives spatial and material form to the cultural geography of Ulster. Overall, Evans played a vital role as both a trustee of the museum and as a mentor to key figures such as George Thompson (the first director of the Folk Museum) and Alan Gailey (Thompson’s successor), who were both fundamental to the realisation of the Ulster Folk Museum.

Emyr Estyn Evans began his academic journey studying geography at Aberystwyth University during the 1920s, under the guidance of H. G. Fleure. From 1928, he went on to spend his academic career at Queen’s University Belfast, where he worked to single-handedly establish the first geography department in Northern Ireland. Central to Evans’ scholarship and philosophies was the notion that deep-rooted continuities in Ireland provided the foundation for a cultural unity that transcended the island’s many regional differences. For Evans, borders were not rigid divides but zones which enabled contact, exchange, and negotiation. The establishment of the internationally significant Irish Folklore Commission - a government-funded organisation established in 1935 with the purpose of collecting, documenting, and preserving the cultural heritage, folklore, and oral traditions of Ireland - likely served as an impetus for Evans, encouraging him to take further action at Queen’s. Additionally, the commission potentially influenced Evans in his leading role in the re-establishment of the third series of the Ulster Journal of Archaeology in 1938 - as part of his broader effort to document, interpret and salvage regional traditions. Over these decades, Evans established himself as a leading figure in both geography and archaeology within the post-partition academic landscape of Northern Ireland. At the same time, influential scholars in the Irish Free State were writing on traditions within Irish culture. In his seminal work The Hidden Ireland, Daniel Corkery highlighted the Catholic peasantry as the central bearers of the nation’s cultural memory, whilst Daniel Binchy’s study on Gaelic law and medieval society presented a continuous Gaelic past that provided the foundations to Irish identity. Similarly, the work of the Irish Folklore Commission focused on collecting rural traditions as expressions of Irish heritage. In Northern Ireland, unionist writers such as Ronald McNeill in his work Ulster’s Stand for Union portrayed protestants as an arguably homogenous community united in their resistance to Home Rule in Ireland. Within this intellectual landscape, both nationalist and unionist narratives emphasized cultural singularity - thus making Evans’ approach distinctive as he placed emphasis within his scholarship, as well as in his realisation of the Ulster Folk Museum, on the geographical complexity of Northern Ireland as being comprised of miniature environments which differed considerably.

Evans was instrumental in advocating for the creation of a national cultural institution in Northern Ireland due to the national institution vacuum caused by the 1921 partition of Ireland: a key potential genus for the establishment of the Ulster Folk Museum. Evans identified this absence as a driving force behind a growing interest in folklife studies in Northern Ireland, a movement he helped to shape and promote. Evans’ concern for the disappearance of traditional ways of life in Ulster led to the formation of the Ulster Folklife and Traditions Committee in the 1950s, a group which began collecting crafts, oral histories, and everyday material culture from across the region. His co-founding of the Ulster Folklife journal in 1955, early support for the Archaeological Survey of Northern Ireland, and role as a founding member of the Northern Irish Tourist Board all reflect the lasting impact of his scholarship, institutional leadership, and public engagement. Evans’ efforts would ultimately contribute to the establishment of the Ulster Folk Museum – a lasting testament to his vision of preserving and interpreting the region’s cultural heritage.

The idea of an open-air museum had already taken hold across Europe, with the Ulster Folk Museum forming part of a broader European movement influenced by Scandinavian examples like Skansen and institutions such as St Fagans in Wales. These institutions set out to present and preserve disappearing buildings, material culture, and traditions of rural ways of life threatened by modernisation and urbanisation. The founders of the Ulster Folk Museum, particularly Evans and Thompson, sought to emulate this approach whilst making their Cultra site regionally specific to Ulster. They envisioned a Folk Museum which would showcase the region’s cultural and environmental diversity through lived experience and vernacular architectural form.

Following years of committee work, legislative action, and political lobbying, the Ulster Folk Museum Act was passed in 1958. Under this act, a board of trustees was formed, and land was acquired at Cultra: a site chosen for its varied landscape with its topography allowing for distinct town, hill, and country areas. Reconstruction of primarily original buildings began in the 1960s, with Duncrun Cottier’s House as the first exhibit building to open on site in 1963. This building highlighted the museum’s early focus on pre-industrial vernacular architecture and represented Evans’ founding vision for the Folk Museum; a museum that not only preserved artefacts but embedded them within their social and geographical context. This early phase of development culminated with the opening of the Ulster Folk Museum in 1964, realising an ambitious project long championed by Evans.

The Ulster Folk Museum’s rural area was the first part of the site to be developed, with two early buildings – Duncrun Cottier’s House and Corradreenan Farmhouse – offering insights into how Evans’ ideas are realised onsite to this day at the museum. Each building highlights distinct architectural forms, lived experiences, and social histories shaped by their original environments. Duncrun Cottier’s House, built around the mid-eighteenth century, came from a remote area in north-west County Derry/Londonderry in the townland of Duncrun. The house is a modest two-roomed cottage with a thatched roof supported by bog oak cruck trusses, turf-lined walls, and a wattled chimney hood. Buildings such as the Cottier’s House would have been of particular interest to Evans and the museum’s staff as it was reputed to be one of the oldest surviving vernacular dwellings in its locality. Originally reconstructed at the entrance of the Folk Museum due to financial stringencies, Duncrun was later reconstructed beside a rural lane to echo its original roadside setting. The building’s social history, likely one of hardship and ingenuity, deepens its meaning. Therefore, the house is illustrative of one strand within Ulster’s wider cultural identity and acts as a reminder of the disappearing traditions that Evans sought to preserve on site at the Folk Museum. During the early 1900s, the period to which the entire museum is interpreted, the Clyde family occupied the house; the men of the house working as agricultural and railway workers and the women as seamstresses. Importantly, oral histories from members of the Clyde family have described Margaret Clyde’s resourcefulness through baking soda bread, growing fruit and vegetables in the garden, and saving flour sacks to make quilts for winter. Margaret’s nephew, traditional singer Eddie Butcher, later drew inspiration from this environment in his songs. As Hugh Shields, a close friend of Butcher, recounts ‘Eddie’s spoken lore – sayings, riddles etc. – evokes the rural domestic scene more than anything else’ as ‘singing and talk were among the best restoratives’ … ‘nights spent in common at the fireside – ‘caleying’ for the visitors – gave plenty of listening time.’ These oral recollections of Duncrun add another dimension to the house’s historical interpretation, highlighting how material space and intangible tradition intersect across the buildings at the Folk Museum.

In Contrast, Corradreenan Farmhouse from County Fermanagh presents a more prosperous rural narrative. Originally built about 1750 and improved over time, the farmhouse was home to the Elliot family until the 1930s. Corradreenan features a hipped thatch roof, a bedroom with a tester bed, and a spyhole built into the jamb wall suggestive of a growing concern for comfort and privacy. The farmhouse’s architecture reflects both the family’s economic stability and the broader overlap between rural and domestic design in the early twentieth century. Set against the modest Duncrun dwelling, Corradreenan exemplifies Evans’ argument that Ulster was made up of differing regional experiences, as opposed to a singular experience of one homogenous society. Crucially, reconstruction of the farmhouse at the Folk Museum in 1970 was supported by oral testimony from former occupant Alice Elliott, who described the house’s layout and furnishings. These key contributions ensured that the house was not only structurally accurate but true in its depiction of everyday life in the early 1900s through its interior design. Overall, the two case studies illustrate how Estyn Evans’ concept of Ulster as a province of miniature environments, which each yield unique human experiences, is evident across the site of the Folk Museum. While Duncrun and Corradreenan reflect distinct regional experiences, one of precarity and one of relative prosperity, the buildings are unified through their vernacular origins and hold strong links to cultural memory. Both houses were built with local materials, shaped by their occupants’ labour, and sustained by communal traditions.

In conclusion, Estyn Evans must be recognised not merely as a scholar of archaeology, geography, and folklife studies, but as the intellectual architect behind the Ulster Folk Museum. Evans’ vision, rooted in the belief that regional differences enrich rather than divide, is illustrated through how Northern Irish cultural identities are represented on site at the Folk Museum. By creating a museum landscape which showcases vernacular diversity, Evans’ work offered an inclusive, pluralistic model of heritage. Whilst Evans’ contemporaries placed emphasis on distinct traditions as the essence of Irish identity, at the Folk Museum Evans placed his emphasis on regional diversity, continuity, and everyday life. The case studies of Duncrun and Corradreenan reveal how Evans’ approach shaped both the spatial and curatorial decisions of the museum, as the buildings tell stories of class, locality, material culture, and cultural memory. In situating buildings within landscapes which echo their original environments, the museum today operates as both an archive and an argument for the cultural heterogeneity of Ulster. Today, as the Ulster Folk Museum undergoes its ‘Reawakening’ project, to expand its role as a heritage and environmental resource, to make it more relevant and resilient for current and future generations, Evans’ founding ethos remains essential. In an increasingly divided and globalised world, Evans’ pioneering model of heritage as both a shared and regionally distinctive concept offers a powerful framework for understanding community, identity, and place. He offered a new and broader vision of cultural heritage.

Further Reading:

Emyr Estyn Evans, ‘Folklife Studies in Northern Ireland’, Journal of the Folklore Institute, 2.3 (1965), 355–363.

Emyr Estyn Evans, Mourne Country: Landscape and Life in South Down, 2nd rev. edn (Dundalk: Dundalgan Press, 1967).

Marcus W. Heslinga, The Irish Border as a Cultural Divide: A Contribution to the Study of Regionalism in the British Isles (Assem: Van Gorcum, 1962).

Simon J. Knell and others, National Museums: New Studies from Around the World (London: Routledge, 2010).

Carys Tyson-Taylor is currently undertaking a CDP studentship with National Museums NI and University of Leicester. Her doctoral project titled ‘A tragedy not to preserve now, while there is still time’ – the establishment of a Folk Museum for Ulster, 1929-1964’, aims to produce a critical and nuanced analysis of the establishment and early development of the Ulster Folk Museum, exploring how an understanding of its history might contribute to shaping its future. Her research examines the Folk Museum’s founding ethos and the key motivators behind its conception – particularly in the context of the Reawakening project – as she explores how these learnings may support and inform the Folk Museum’s current and future development. Currently based at the University of Leicester, Carys is looking forward to relocating to Belfast for the upcoming academic year – enabling her to work more closely with the museum and gain greater access to the archival resources crucial to her study.